TALENTED KIDS: Music for two harpsichords

The Four Nations Ensemble

Saturday, October 8th at 2:30 PM

Stanfordville, NY

THE ARTISTS

Alberto Busettini & Andrew Appel, harpsichord

Olivier Brault, violin

Loretta O'Sullivan, cello

THE PROGRAM

Sonata in G major for two harpsichords, J. C. Bach

Allegro--Tempo di Menuetto

Sonata in E minor for violin & continuo, J. S. Bach

Adagio ma non tanto—Allemande—Gigue

Four pieces for two harpsichords, C. P. E. Bach

Allegro—Poco Adagio—Poco Adagio—Allegro

Sonata in F major for two harpsichords, W. F. Bach

Allegro—Andante—Presto

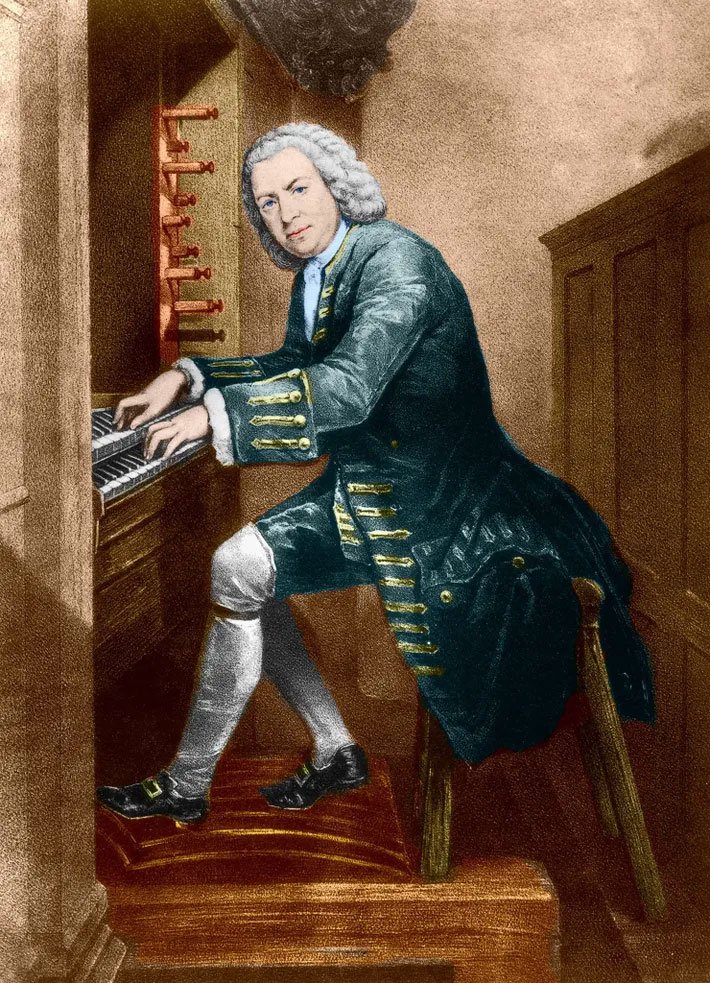

Musical dynasties are not unique in history. The Couperins span the 17th through 19th centuries. In our own day, Rudolf and Peter Serkin cover two generations of monumental pianism. But the Bach family stands as the most miraculous of all dynastic family trees.

Though a miracle, it is not a surprise that into this family, known for three centuries of musical genius, a specific generation would demonstrate a flowering beyond all others in the Bach tree. We might expect that the branch of Johann Sebastian was that particularly important one, but we would be incorrect. Without doubt, Johann Sebastian was the greatest of composers, but it was among his 20 children that we find brother-composers who were pivotal in the history of music. Johann Sebastian Bach boasted that he could form a fine orchestra from his own kids. But with his strongly held conservative tastes and demands, I doubt he recognized the importance of his children. Of the four boys who became respected professionals, Carl Philipp Emanuel was the harbinger of Romanticism and the idol of philosophers from every corner of Europe. John Christian, elegant, lyrical, constantly beautiful, and filled with wit and subtle art, served Mozart as model. John Christian Bach can also be recognized as the pioneer concert entrepreneur, understanding and responding to the tastes of his vibrant public and creating a business model that is our method of enjoying live music today: the subscription series.

Johann Sebastian was committed to his children's education and obsessed with his oldest and favorite, Wilhelm Friedemann. It was from the keyboard that a path was carved for this long-fingered prodigious child with works including the Wilhelm Friedemann Notebook, the 2 and 3-part Inventions, and the Well Tempered Clavier. Friedemann’s pace of development, as charted in these works, is astounding. Friedemann must have thrilled his father as he mastered technical and musical challenges at lightning speed. The evidence for his unique virtuosity is evidenced in the portraits of each son and father. While Friedemann has long, graceful fingers, the other Bachs show hands with short, sausage-like digits. And of all the compositions of the Bach sons, Friedemann’s technical demands far outweigh the challenges from his brothers. His pieces and concertos are difficult...devilishly so!

Yet, being the favorite created difficulties for the son. The spotlight given to him by his father was scorching. It was difficult for him to cultivate his unique personality. He could not rebel (as every generation must) from his parent and establish a separate path. Friedemann’s music is often thrilling, complex, intelligent, and attractive. He is subject to moods and uses them to create an almost neurotic intensity through sound. His florid, embellished melodies are crystals of German Rococo or emfindsamkeit music…Super sensitive.

Attesting to its quality of composition, the Sonata for two harpsichords in F Major was mistaken for a work by Johann Sebastian. It is prophetic and demonstrates one of the first fully developed sonata forms that would become the main architecture for Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven. As satisfying as this work is, it could not surpass the works of his father nor serve as a genesis for a new style of music. No matter, this sonata is one of the finest works for two keyboards in our repertory.

If Wilhelm Friedemann could master everything his father wrote for his education, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach complains of the preludes and fugues from the Well Tempered Clavier, admitting that he was never able to master them all. They were too difficult. Old Bach was not complimentary of the new music coming from Carl Philipp and his colleagues. He called it “Prussian Blue,” a dye of rich hue that fades when exposed to sunlight. The implication was that under scrutiny, this new music was shallow and dull.

Of course, mediocrity exists in every style, and Old Bach may have had a point with much of this new music, but it would be inaccurate to condemn his son on those terms. Carl Philipp is the exponent of the values of personal expression. “I write what I feel and when I feel like it.” He is the master of the unpredictable and sublime in music. Mercurial and constant surprise is his character and anything solid or predictable is toxic. Similar to Goethe’s Faust, contentment equals death, and a long, relaxed plateau of beauty is tantamount to meaninglessness, dishonesty, and boredom. Mozart tells us that modern music could not be what it is without Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, but that his music had become old-fashioned, no longer viable.

Like his godfather Telemann, Carl Philipp wrote music for different audiences: the connoisseur and the amateur. He challenged the knowing musician with works that still demand much from today’s performers, yet, as in the four duets for two harpsichords, he was able to write succinct and very comprehensible recreational music for the sons and daughters of a rising merchant and middle class of Hamburg and Berlin.

Carl Philipp asked his younger brother John Christian, why he wrote music for children to which John replied that he was supplying his audience with the music they preferred. And though John Christian’s music is as delicious as warm trifle on a cold day, we must not make the mistake of thinking it is music of little genius. The instability and disturbing emotionalism of Carl Philipp would be found ugly and distressing in John Christian’s London. This is the city and country well past all violent revolutions, in a steady economic climb towards powerful empire, enjoying the benefits of advanced medical discoveries and general knowledge. The ladies and gentlemen who subscribed to Bach’s concerts were out of Thomas Gainsborough’s and Joshua Reynolds’ portraits. They were as sweetly triumphant as the sharp-witted and kind-hearted characters in Sense and Sensibility.

In the secure and joyful sonata for two keyboards in G major we find subtle manipulations, the smallest details that keep the music fresh and our attention focused. The accompaniment might have one unexpected note that changes the weight of a phrase. John Christian may draw a chord with a gently dissonant note that increases color and inspires a sentimental frisson. Pleasure is the purpose and a constant in his music. His sonatas and concertos celebrate and laugh, sin and sigh, console and assure. His movements are generous and lovely.

It is accepted truth that great teachers do not produce versions of themselves, but empower students with the skills needed to carve personal paths. With Johann Sebastian’s E minor violin and continuo sonata, a magnificent example of the Baroque composer’s attitude towards melody, harmony, graceful stability and/or improvisation, we have a reference point that loudly proclaims the independence, power, and well-schooled genius of these talented kids.

Andrew Appel

Craryville, NY

September 27, 2022