Five Parts and Foreign Influences

The Four Nations Ensemble

Thursday, January 19, 2023, at 7:30 PM

Church of the Heavenly Rest

THE ARTISTS

Pascale Beaudin, soprano

Olivier Brault & Chloe Fedor, violin

Nicole Divall & Kristin Linfante, viola

Loretta O’Sullivan & Keiran Campbell, cello

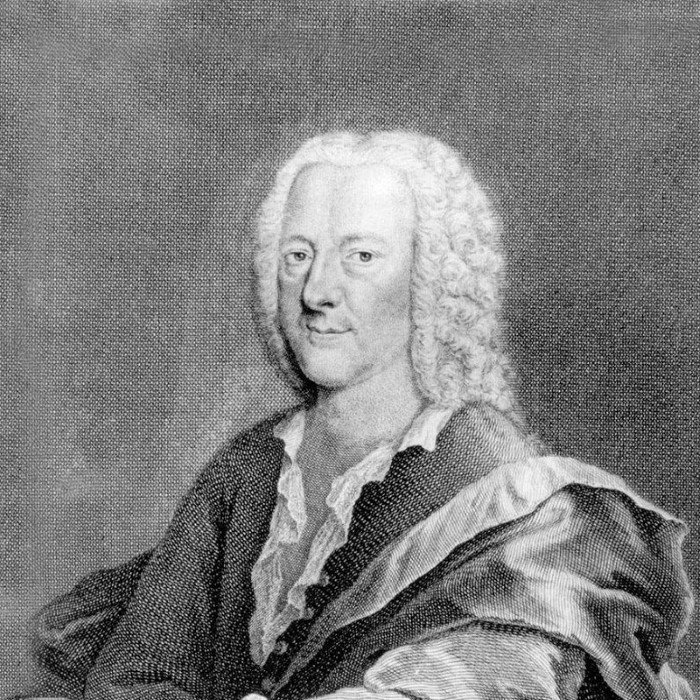

Andrew Appel, harpsichord

THE PROGRAM

Georg Muffat * Sonata V Armonico Tributo

Johann Christophe Bach * Mein Freund ist mein

Johann C. F. Fischer * Overture I in C major Journal du Printemps

Johann Jakob Froberger * Toccata & Tombeau

Johann Sebastin Bach * Heute Noch The Coffee Cantata BWV 211

G. A. Brescianello * Ciaccona in A major

There are specific works of art that on first acquaintance affect us like a bolt of lightning or a joyful revelation: The Birth of Venus, The Sistine Chapel and Notre Dame de Paris, Chaplin’s City Lights, Hamlet. So it is with Muffat’s Passacaglia, the final movement of his fifth sonata from Armonico Tributo, the music that opens Four Nations’ New York Season. I was astonished with its power, complexity, contrasting beauties, and ability to excite and move. Without diminishing him in any way, Muffat puts Bach in context, in his place. And this passacaglia illustrates the alchemy of combining traits from Italy and France to create an international style. It underlines the ability of certain German composers to elevate a sense of meaning and unexpected importance behind the notes.

One ingredient in this masterful work is the five-part ensemble. Rather than the usual ingredients of two violins, viola, and bass, Muffat includes a second viola, enriching the work from the middle register. This creates, at his command, a feast for the ear. We recall that Muffat lived in Paris studying with Lully and listening to Lully’s five-part orchestra. With this, Muffat also mastered the grace and sensuality of French dance, lending his Passacaglia an infectious fluidity.

Muffat chooses to alternate between lean forces and full ensemble, turning this passacaglia into a concerto grosso. We recall that Muffat lived in Rome as well as Paris, working with Corelli and digesting the art of the new concerto. For Corelli, the concerto included a trio of soloists alternating with an orchestra that doubled the soloists, playing the very same notes to enrich the sonority. Muffat incorporates this variety of texture and adds to it a violin virtuosity that is purely Italian.

Finally there are Muffat’s native inclinations. There is his contrapuntal complexity, his thrilling ability to layer materials one on top of another and to call upon a skillful and beguiling science of music borrowed from no other national style but the genius of German organists, late flowers of the Renaissance.

Listen as Muffat repeats the melody of the first eight measures several times in the course of this long work to create a tangible architecture, recalling the French rondeau form and predicting Bach’s violin chaconne. In the voyage through this piece there are fanfares, lamentations, recitations, flights of fancy, and the fire of a virtuoso. Yes, hearing this work for the first time is a lightning bolt!

French style, much of it imported to Germany by Protestant refuges landing in small courts throughout the Lutheran world, employed to play dance music in five-parts for bumpkins trying to be sophisticates. This music was appreciated for its gallant simplicity. Neither too learned nor complex but easy to understand and digest. Johann Fischer’s collection of five-part orchestral suites is well titled Journal du Printemps. This is music for celebration, for toy soldiers and masqueraders. Never insipid because beautifully composed, these works are akin to an astonishing wedding cake, the masterpieces of a great pastry chef.

The virtuosity exhibited in the Passacaglia of Muffat has its origins in the hands of Italian itinerant fiddlers who traveled from one feast to another improvising on well-known dance tunes and thrilling revelers at weddings with unruly, indecorous, rule-breaking music. They were the jazzing talents of their day and appropriately, Bach’s uncle Johann Christophe incorporates this sort of fiddling in his celebratory wedding cantata. He sets the erotic lines of the Song of Songs quite simply but writes a series of dizzying elaborations for the bad boy violin accompanied by three violas serving as a back-up group.

Muffat finds his traveling counterpart in Johann Jakob Froberger who sojourned in Italy, France, and England. On these long stays he incorporated the mercurial keyboard character of Frescobaldi, the delicacy of the French lute and harpsichord styles of Louis Couperin and worked them into a personal style unique for its emotional exhibitionism. There is a stream of consciousness in Froberger’s work in which he invites us to witness his spleen, anxiety, and frustrations. There is honesty in his music that the French harpsichordist would find uncomfortable. He is a prophet of romantic self-preoccupation reminiscent of Dürer and his self-portraits.

Two generations later an Italian immigrant to Munich, Giuseppe Antonio Brescianello is convinced of the German’s inclination to work alchemy, combining styles. For him, the metal of his exquisite chaconne is made of the sensuality of Rameau combined with the vitality of Vivaldi. The first time I heard this work by a relatively unknown composer, I was confounded. Who wrote this? Where is it from?…and like the Muffat Passacaglia, I was tickled, delighted and moved. Hearing this work for the first time is a lightning bolt.

And so, for our first concert of 2023 in New York, all of us at Four Nations want to start your year with a few selected and beloved bolts!

Andrew Appel

January 1, 2023

Craryville, NY